Placing the field label inside the field for the user to type over may save space, but it also causes your label to disappear once the user interacts with the field.ĥ. This “stacked” format suits the portrait orientation with which most smartphone users hold their device. Place the field label above, and left justified with, any field requiring the respondent to type. (And you already know that short and direct is best, right?) The wide variety of serifs in existence make character-recognition more difficult to non-native readers, while san serifs are more likely to remain readable when scaled down.Ĥ. Why? While studies do not point to a clear winner for readability in all contexts, evidence suggests that lengthy text passages that ask the reader to parse several ideas at once are best served by serif fonts, while short prompts and labels are best conveyed with a sans serif font. If you have a choice of fonts, sans serif is preferable. For section headings and buttons, a vibrant color that contrasts sufficiently with the background can help orient the respondent.ģ. Black or dark grey text on a white background is always the safest default for instructions and form labels. Here are some pointers on visual cues that work with the eyes and minds of your participants:Ģ.

#Epro ontime free

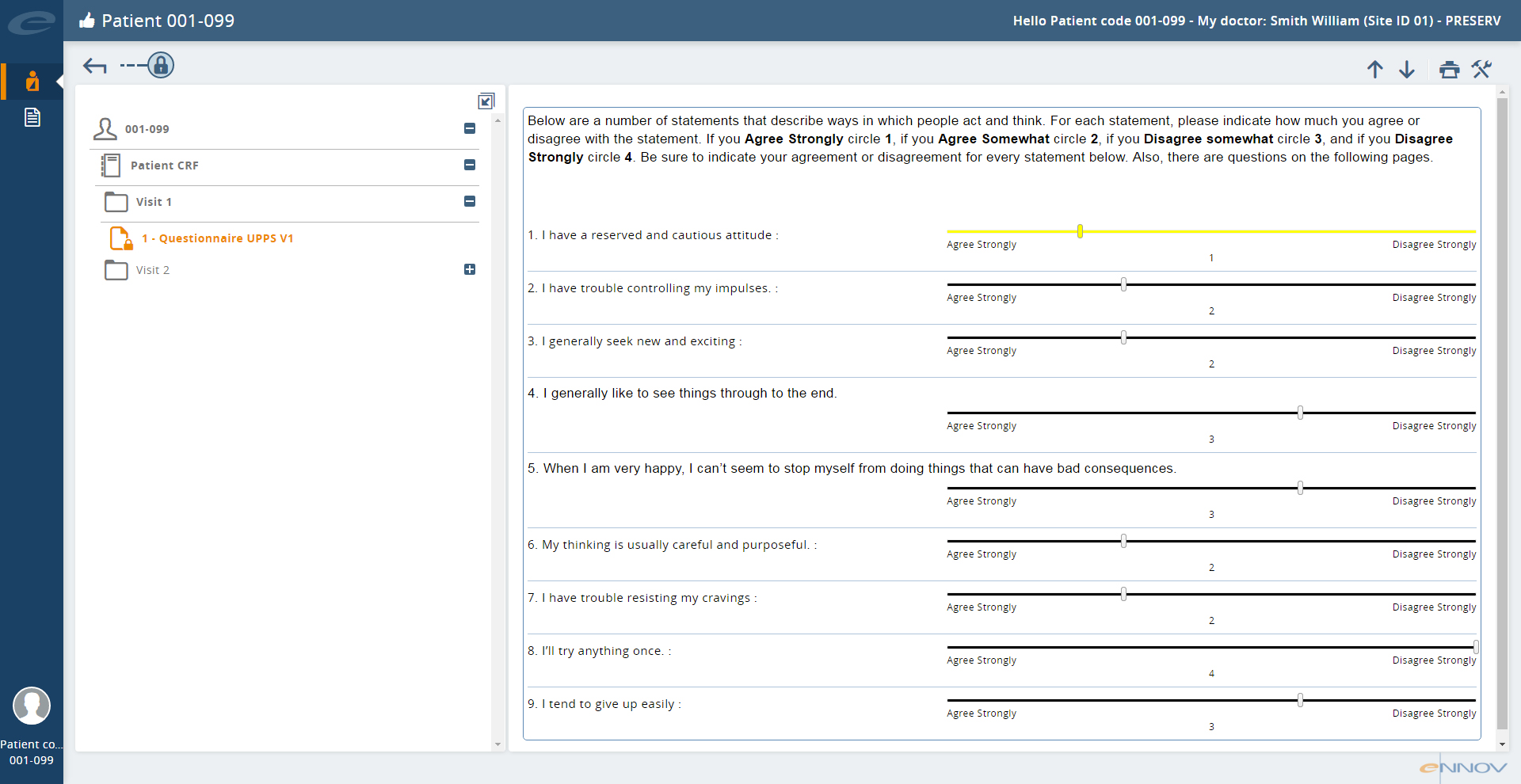

In short, you’re free to give respondents a form-reading and form-filling experience they actually enjoy. Spatial and color constraints no longer apply, and you can present information in a way that prevents the participant from looking ahead (and becoming discouraged). The “e” in “ePRO” isn’t usually capitalized, but maybe it ought to be. Yes, the latter scenario involves more clicks, but it involves less cognitive labor and less scrolling. Rather, ask two yes or or no questions that will reduce the options first to eight and then four, and have the user pick from that list. Don’t ask the participant to choose one of sixteen options. This best practice is one example of a broader rule: always proceed from the simple to the complex. Present these one to three questions, and no more, on the first page. Start with a single (or very small number) of questions that can be answered simply. The lesson for ePRO form design is clear.ġ.

“Tell me, what’s your top priority in your current role?” She’ll need to gather a lot more information before the end of the interview, but she’s set out a comfortable pace for getting it. How coherent will you answer be? A practiced interviewer, interested in getting to know you, would start differently. The hiring manager asks you to rattle off the top three responsibilities in every role you’ve ever filled. Below, I bundle them into four categories.

#Epro ontime pro

So, what are the keys to getting your participants to enter all their PRO data, accurately and on time? Not surprisingly, they’re not too different from those we rely on in any budding relationship. What good are friendly, motivational messages to a participant’s mobile device and computer, if the form to which they’re directed is needlessly long or convoluted? That’s a recipe for heartbreak (form abandonment), or at least a host of trust issues (incomplete or poor quality data). In previous posts, we explored BYOD as a preferred approach to collecting ePRO data. Not if we want to maximize their contribution. As an industry, we can’t stop looking for ways to minimize the burden on participants. Paper diaries and even electronic forms ask a participant for their time and attention, goods that are in short supply these days. But that “quid pro quo” mindset isn’t easy to maintain outside the clinical site.

That’s not to say that the care provided in the course of a study isn’t of value to patients. A participant’s compliance with study procedures (and data entry) is always only voluntary, and apart from the occasional stipend, these participants rarely receive compensation in dollars. Sadly, it’s just one problem among dozens that hinder the collection of timely, clean and complete data directly from study subjects. Sometimes, it’s hard not to take that kind of rejection personally.

Is there any term in data collection more despairing than “abandonment rate”? That’s the percentage of respondents who start inputting data into a form but don’t complete the task.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)